John Edward – A study on Transitivity, Point of View, and Affect in the Eighth Chapter of William Maxwell’s “The Folded Leaf”

The Folded Leaf, Chapter 8

- 1- Mr. Peters’ apartment

Two pictures stood side by side on Lymie Peters’ dresser. The slightly faded one was of a handsome young man with a derby hat on the back of his head and a large chrysanthemum in his buttonhole. The other was of a woman with dark hair and large expressive dark eyes. The picture of the young man was taken in 1897, shortly after Mr. Peters’ nineteenth birthday. The high stiff collar and the peculiarly tied, very full four-in-hand were bound to have their humorous aspect twenty-six years later. The photograph of Mrs. Peters was not a good likeness. It had been made from another picture, an old one. She had a black velvet ribbon around her throat, and her dress, of some heavy material that could have been either satin or velvet, was cut low on the shoulders. The photographer had retouched the face, which was too slender in any case, and too young. Instead of helping Lymie to remember what his mother had looked like, the picture only confused him.

He had come into the bedroom not to look at these pictures but to see what time it was by the alarm clock on the table beside his bed. The room was small, dark, and in considerable disorder. The bed was unmade. A pair of long trousers hung upside down by the cuffs from the top drawer of the dresser, and the one chair in the room was buried under layers of soiled clothes. On the floor beside the window was a fleece-lined bedroom slipper. There was fluff under the bed and a fine gritty dust on everything. The framed reproduction of Watts’ “Hope” which hung over the dresser was not of Lymie’s choosing. During the last five years Mr. Peters and Lymie had lived first in cheap hotels and then in a series of furnished kitchenette apartments, all of them gloomy like this one.

The grandfather’s clock in the hall and the oriental rug on the floor in Lymie’s room had survived from an earlier period. The rug was worn thin and curled at the corners, but when Lymie turned the light on, the childlike design of dancing animals—dogs, possibly, or deer, worked in with alternating abstract patterns—was immediately apparent, and the colors shone. The grandfather’s clock remained at twenty-five minutes past five no matter what time it was, but the alarm clock was running and it was seven-twenty.

- 2- Lymie shaves

Lymie went into the bathroom and moved the pieces of his father’s safety razor, the rusted blade, the shaving brush, and the tube of shaving soap, from the washstand to the window sill. He let the hot water run a moment, full force, to clean out the bowl, and then he washed his face and hands and ran a wet comb through his unruly hair. The arrangement was that if his father didn’t come home by seven – thirty, Lymie was to go to the Alcazar Restaurant on Sheridan Road and eat by himself.

- 3- Lymie heads to the Alcazar Restaurant

At exactly seven-thirty-one he let himself out of the front door of the apartment building. The other boys in the block had had their dinner and were outside. Milton Kirshman was bouncing a rubber ball against the side wall of the building. The others were in a cluster about Gene Halloway’s new bicycle. They nodded at Lymie, as he went by. The bicycle was painted red and silver and had an electric headlight on it which wouldn’t light. A slight wind blew the leaves westward along the sidewalk, and there were clouds coming up over the lake.

- 4- The Alcazar restaurant and the history book

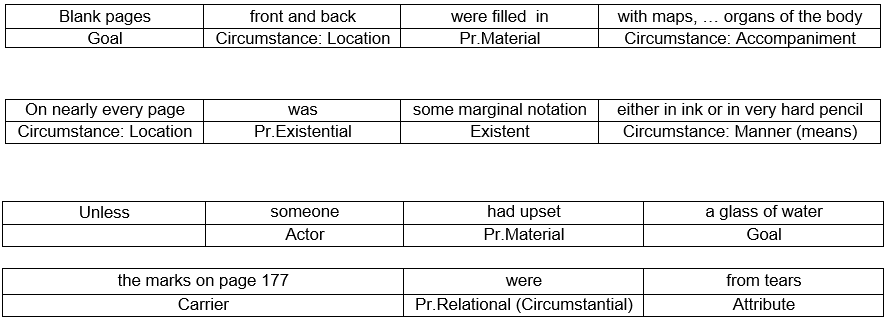

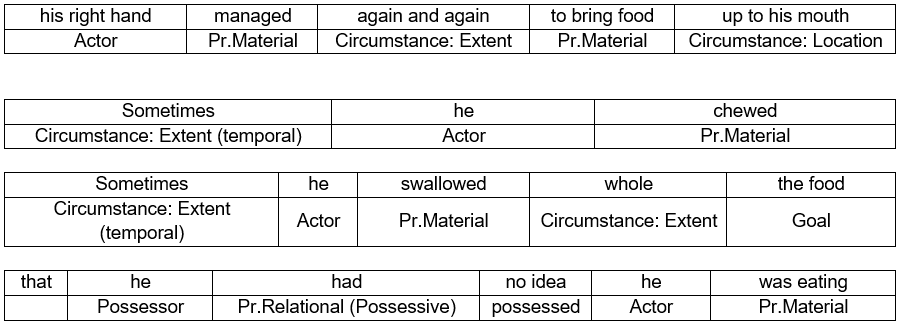

The Alcazar Restaurant was on Sheridan Road near Devon Avenue. It was long and narrow, with tables for two along the walls and tables for four down the middle. The decoration was art moderne, except for the series of murals depicting the four seasons, and the sick ferns in the front window. Lymie sat down at the second table from the cash register, and ordered his dinner. The history book, which he propped against the catsup and the glass sugar bowl, had been used by others before him. Blank pages front and back were filled in with maps, drawings, dates, comic cartoons, and organs of the body; also with names and messages no longer clear and never absolutely legible. On nearly every page there was some marginal notation, either in ink or in very hard pencil. And unless someone had upset a glass of water, the marks on page 177 were from tears.

- 5- Lymie reads the history book

While Lymie read about the Peace of Paris, signed on the thirtieth of May, 1814, between France and the Allied powers, his right hand managed again and again to bring food up to his mouth. Sometimes he chewed, sometimes he swallowed whole the food that he had no idea he was eating. The Congress of Vienna met, with some allowance for delays, early in November of the same year, and all the powers engaged in the war on either side sent plenipotentiaries. It was by far the most splendid and important assembly ever convoked to discuss and determine the affairs of Europe. The Emperor of Russia, the King of Prussia, the kings of Bavaria, Denmark, and Wurttemberg, all were present in person at the court of the Emperor Francis I in the Austrian capital. When Lymie put down his fork and began to count them off, one by one, on the fingers of his left hand, the waitress, whose name was Irma, thought he was through eating and tried to take his plate away. He stopped her. Prince Metternich (his right thumb) presided over the Congress, and Prince Talleyrand (the index finger) represented France.

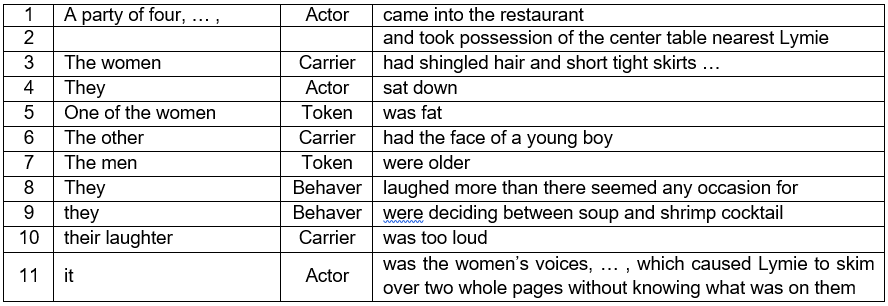

- 6- The party of four

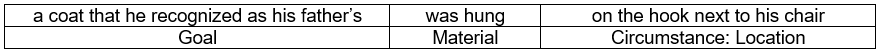

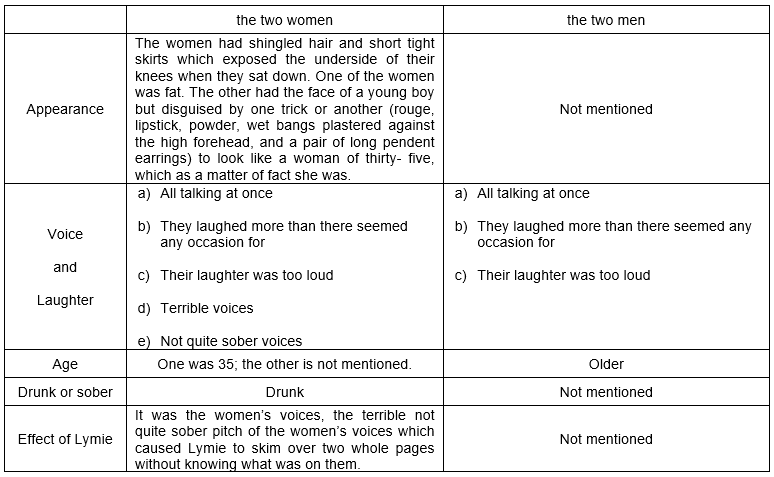

A party of four, two men and two women, came into the restaurant, all talking at once, and took possession of the center table nearest Lymie. The women had shingled hair and short tight skirts which exposed the underside of their knees when they sat down. One of the women was fat. The other had the face of a young boy but disguised by one trick or another (rouge, lipstick, powder, wet bangs plastered against the high forehead, and a pair of long pendent earrings) to look like a woman of thirty- five, which as a matter of fact she was. The men were older. They laughed more than there seemed any occasion for, while they were deciding between soup and shrimp cocktail, and their laughter was too loud. But it was the women’s voices, the terrible not quite sober pitch of the women’s voices which caused Lymie to skim over two whole pages without knowing what was on them. Fortunately he realized this and went back. Otherwise he might never have known about the secret treaty concluded between England, France, and Austria, when the pretensions of Prussia and Russia, acting in concert, seemed to threaten a renewal of the attack. The results of the Congress were stated clearly at the bottom of page 67 and at the top of page 68, but before Lymie got halfway through them, a coat that he recognized as his father’s was hung on the hook next to his chair. Lymie closed the book and said, “I didn’t think you were coming.”

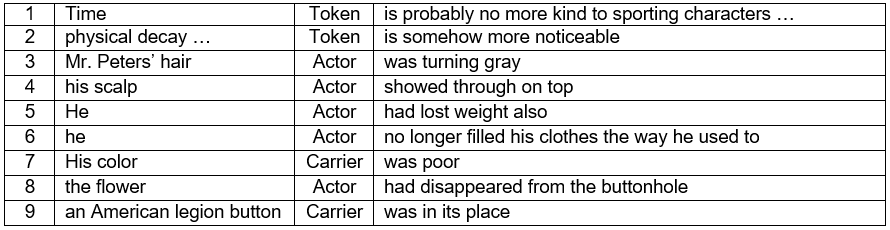

- 7- The arrival of Mr. Peters

“I got held up,” Mr. Peters said. He put his leather brief case on a chair and then sat down across the table from Lymie. The odor on his breath indicated that he had just left a prospective client somewhere (on North Dearborn Street, perhaps, in the back room of what appeared to be an Italian pizzeria but was actually a speakeasy); his bloodshot eyes and the slight trembling of his hands were evidence that Mr. Peters drank more than was good for him.

- 8- The aging Mr. Peter

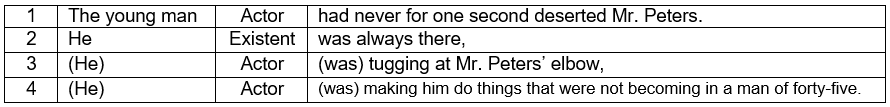

Time is probably no more unkind to sporting characters than it is to other people, but physical decay unsustained by respectability is somehow more noticeable. Mr. Peters’ hair was turning gray and his scalp showed through on top. He had lost weight also; he no longer filled out his clothes the way he used to. His color was poor, and the flower had disappeared from his buttonhole. In its place was an American Legion button.

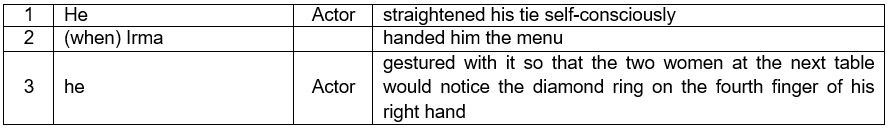

Apparently he himself was not aware that there had been any change. He straightened his tie self- consciously and when Irma handed him a menu, he gestured with it so that the two women at the next table would notice the diamond ring on the fourth finger of his right hand. Both of these things, and also the fact that his hands showed signs of the manicurist, one can blame on the young man who had his picture taken with a derby hat on the back of his head, and also sitting with a girl in the curve of the moon. The young man had never for one second deserted Mr. Peters. He was always there, tugging at Mr. Peters’ elbow, making him do things that were not becoming in a man of forty -five.

- 9- The conversation between Lymie and Mr. Peters

“I won’t have any soup, Irma,” Mr. Peters said. “I’m not very hungry. Just bring me some liver and onions.” He turned to Lymie. “Mrs. Botsford come?”

Lymie shook his head. “Maybe she’s sick.”

“She always calls the office when she’s sick,” Mr. Peters said. “More than likely she’s quit. It’s a long way to come and she may have found somebody on the South Side to work for. If she has quit, she’ll get in touch with me. She’s got four weeks’ wages coming to her.”

“But I thought you paid her last week,” Lymie said.

“I was going to,” Mr. Peters said, “but I didn’t get around to it.” He glanced at the next table. “What kind of a day did you have at school?”

“All right,” Lymie said.

“Anything happen, specially?”

A whistle blew faintly, Mr. Pritzker’s whistle, and for a moment the splashing surrounded Lymie and sucked him down. He decided that it wasn’t anything that would interest his father. School was one world, home was another. Lymie could and did pass back and forth between them nearly every day of his life, but it was beyond his power to bring the two together. If he tried now, his father would make an attempt at listening but his eyes would grow vague, or he would glance away for a second and hardly notice when Lymie stopped talking.

“No,” Lymie said, “nothing happened.”

Mr. Peters frowned. He would have liked the people at the next table to know how smart Lymie was and what good grades he got on his monthly report card.

There was a long silence during which Lymie might as well have been studying, but he didn’t feel that he should when his father was sitting across from him, with nothing to read and nobody to talk to.

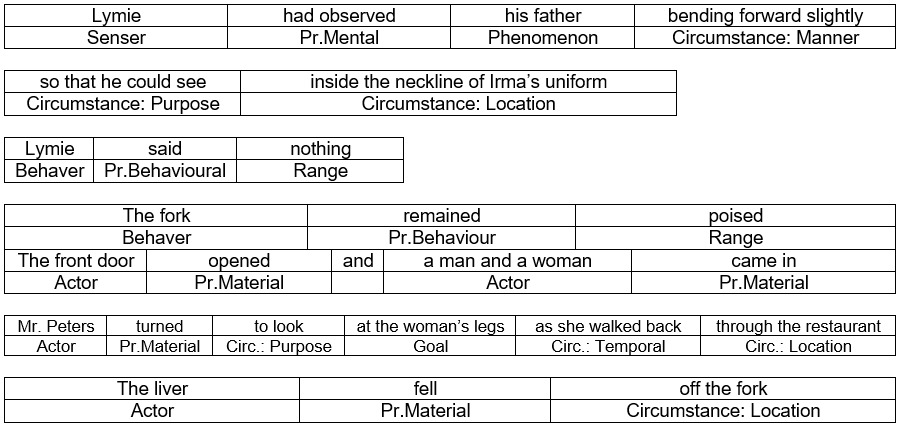

- 10- Irma

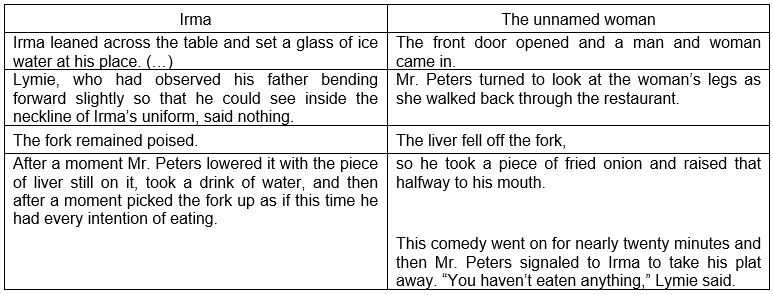

When Irma reappeared with the liver and onions, it was a great relief to both of them. Mr. Peters cut a small piece of meat, stuck his fork into it, and raised it to his mouth. Just as he was about to take the meat from the fork, Irma leaned across the table and set a glass of ice water at his place. He put the fork down, broke off a piece of bread, buttered the bread carefully, and then put it on the tablecloth beside his plate. After that he raised the piece of liver to his mouth again, but instead of taking it he said thoughtfully, “Irma is a very fine girl. Too capable to be doing this kind of work. She ought to be in an office somewhere making twenty- five dollars a week.”

Lymie, who had observed his father bending forward slightly so that he could see inside the neckline of Irma’s uniform, said nothing. The fork remained poised. After a moment Mr. Peters lowered it with the piece of liver still on it, took a drink of water, and then after a moment picked the fork up as if this time he had every intention of eating. The front door opened and a man and woman came in. Mr. Peters turned to look at the woman’s legs as she walked back through the restaurant. The liver fell off the fork, so he took a piece of fried onion and raised that halfway to his mouth. This comedy went on for nearly twenty minutes and then Mr. Peters signaled to Irma to take his plat away.

“You haven’t eaten anything,” Lymie said.

“I wasn’t hungry,” Mr. Peters said. “All I want is some coffee,” and once more there was a long silence, during which each of them searched vainly through his whole mind for something to say to the other.

________________________________________________________________________________

A study on Transitivity, Point of View, and Affect in the Eighth Chapter of William Maxwell’s “The Folded Leaf”

“When a painter by his artistic skill makes us believe that certain objects project from the picture,

while others are withdrawn into the background,

he knows perfectly well that they are really all in the same plane.”

(Quintilian, Institutio Oratoria 2, 16, 21)

- Introduction

According to Quintilian, the eminent first century Roman rhetorician, artistic skills are manifest in how the artist highlights some details and reduces others to the background. When considered in the literary context, the aforementioned dichotomy does not do justice. When it comes to literature, an author does not use colors and brushes; instead, his tools are lexis, grammar, situations, genres, and metaphors (Derrida 1997, p.227 even adds punctuation to the nonphonetic marks of expression) to draw a portrait of each of his characters and to help the reader visualize the scenes as vividly as possible. It can also be said that the silence and the avoidance of the aforementioned elements can be taken as part of the tools used by an “artist” author.

A very helpful enterprise in tracing the underlying patterns and techniques employed by the authors is Systemic Functional Grammar (SFG). “SFG proposes that sentences take the forms they do for reasons that are neither arbitrary nor the result of innate mental structures, but rather for reasons connected with the functions utterances serve” (Zdenek and Johnstone 2008, p.27). Two of the tools which have proven extremely useful in the realm of SFG are Transitivity Analysis and Appraisal Criticism (will be introduced at the beginning of the Affect Analysis part). SFG describes the sentence as a whole, not only the verb and its object (Thompson 2013, p.94); the transitive choice is responsible for conveying the sense of agency, while intransitive choice and passive-voice choice hide agency and shadow the sense of responsibility (Zdenek and Johnstone 2008, p.27). As explained by Halliday, “Transitivity structures express representational meaning: what the clause is about, which is typically some process, with associated participants and circumstances” (Halliday and Mattheissen 2004, p.309).

There are many reasons for studying Transitivity; for example, Fairclough explains that there is “a social motivation for analyzing transitivity [which] is to … work out what social, cultural, ideological, political, or theoretical factors determine how a process is signified in a particular type of discourse” (Ritivoi 2008, p.49). Although this is the foremost concern in Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), which is to analyze discourse to achieve social change, there are other reasons for the study of Transitivity, one of which is to analyze narratives and their underlying rhetorical techniques used for persuasion and to depict the different points of view (POVs) and behaviours of the different characters.

In 1971, Halliday published a study of William Golding’s novel “The Inheritors”. He managed to demonstrate how Golding utilized Transitivity patterns (perhaps unconsciously) to create a contrast between the different worldviews of his characters (Butt and Lukin 2009, p.196). Through this influential study, Halliday managed to demonstrate the wealth of knowledge the study of Transitivity can offer to discourse analysts by bringing to light the linguistic aspects that encode experiences and worldviews. In Discourse and Crisis (2013, p.33), De Rycker and Don explain that not only lexis but also Transitivity patterns do contribute to the shaping of worldviews, the very same idea utilized by Golding to shape the cognitions and worldviews of his different characters.

Within the SFG framework proposed by Halliday, Transitivity falls under the Experiential component of the Ideational Metafunction (Halliday and Mattheissen 2014, p.30), which models and represents the external world through the transmission of ideas, whereby meaning is considered an organization of a set of experiences (Halliday and Mattheissen 2014, p.362). Consequently, Transitivity analysis looks into how different phenomena, such as events, states, and entities, are constructed and described grammatically (Coffin 2006, p.51). According to Fairclough, identifying the patterns of Transitivity allows us to examine which meanings (experiential, relational or expressive) are stressed and which are shadowed (Liu 2008, p.61).

This paper investigates the Transitivity patterns in chapter 8 (2111 words) of William Maxwell’s novel “The Folded Leaf”. After presenting and explaining the numerical data, the paper will (1) investigate how these patterns relate to the Spatial and Psychological POVs of the narrator, the protagonist (Lymie), and Lymie’s father (Mr. Peters); (2) analyze how the main characters react when they encounter women, and how women are depicted and appraised both grammatically and rhetorically.

To conduct this research, the processes expressed through verbs were classified into six categories: Material, Behavioural, Mental, Verbal, Relational, and Existential (Halliday and Mattheissen 2014, p.354); then, the participants and their roles were tagged. The data was turned into graphs and tables then were interpreted to show the significance of the findings and what the author possibly intended to convey through these patterns.

- Findings

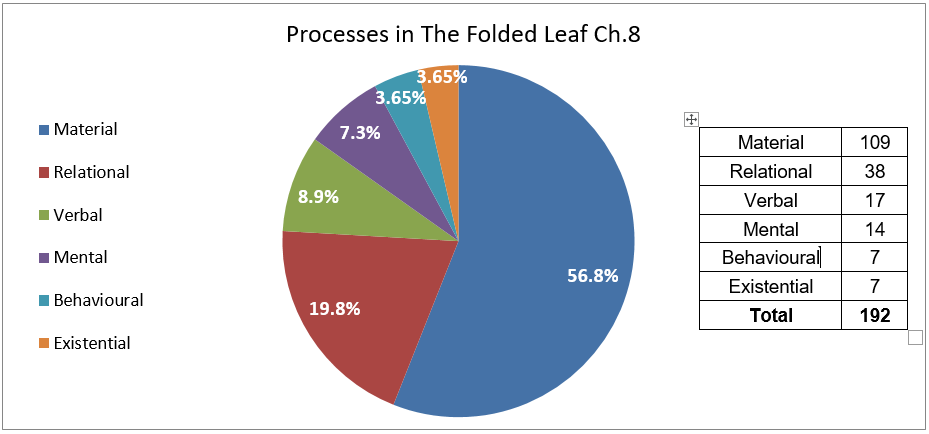

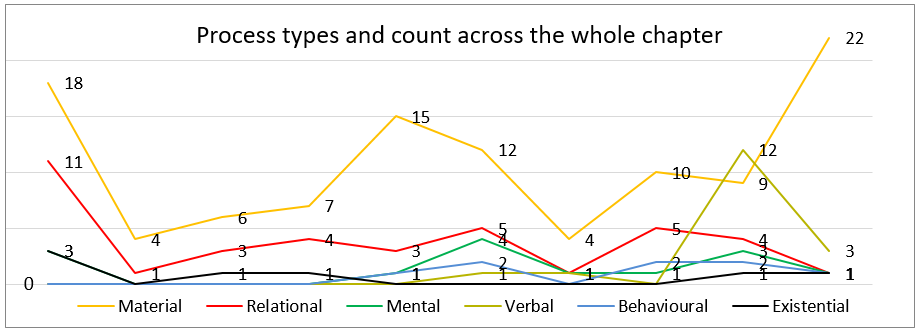

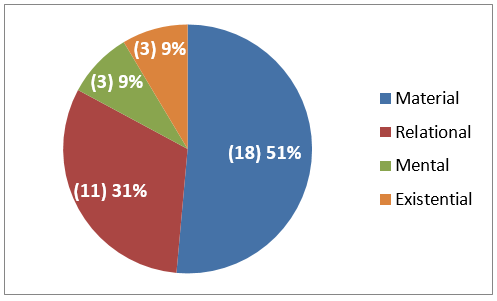

In the eighth chapter, One hundred ninety two processes were manually categorized into the six aforementioned types. The most common process type found is Material processes (109, 56.8%). This type of process is used to express an act of doing, motion, or direction; they always “involve and actor who does something” (Chilton and Schäffner 2002, p.54). It is not surprising that Material processes are pervading in the text because they mainly describe, along with many other things, the actions of Lymie, his journey to the restaurant, the arrival of other customers to the restaurant, the arrival of Mr. Peters, and Irma – the waitress – catering the food to the customers.

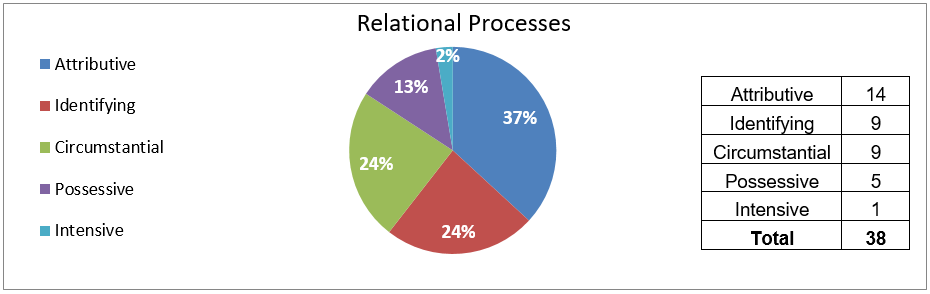

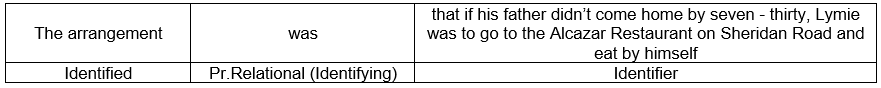

Second in frequency are Relational processes (38, 19.8%), which, according to Coffin (Coffin 2006, p.193), (a) construe different ways of being and having, (b) relate participants to one another, and (c) relate qualities and characteristics to entities. In chapter 8, Attributive Relational (14 out of the 38 Relational processes) processes are used to relate an attribute to a carrier. For example, in “the slightly faded one [picture] was of a handsome man” the carrier is “the slightly faded picture,” the attribute is being “of a handsome man”, and “be” is the process. In a Circumstantial Relational process (9 out of the 38 Relational processes), on the other hand, the attribute is realized by a prepositional phrase (Halliday and Mattheissen 2014, p.290). Identifying Relational processes (9 out of the 38 Relational processes) consist of an Identifier that identifies a certain element (Matthiessen et al. 2010, p.115). In the example below, “the arrangement” is identified by the noun group “that … himself”.

The least common types of Relational processes are possessive Relational processes (5 out of the 38 Relational processes), which indicate that a carrier has/carries an attribute, and intensive Relational processes (1 out of the 38 Relational processes), which “involves establishing a relationship between two terms, where the relationship is expressed by the verb to be or a synonym” (Eggins 2004, p.239).

![]()

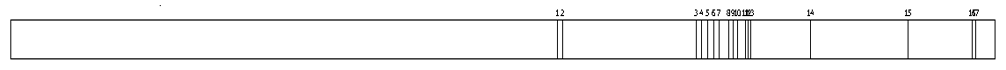

Verbal processes are third in frequency (17, 8.85%). These seventeen occurrences include twelve explicit mentions of the verb “said,” while the other five occurrences were implicit, including verbiage without explicitly using the verb “say”. The seventeen Verbal processes occur in the second half of the chapter, right after Mr. Peters joins Lymie at the table and the their dialogue begins. The table below shows the seventeen occurrences as generated by AntConc 3.5.9.

Mental processes (14, 7.3%) are “processes of feeling, wanting, thinking, and seeing” (Halliday and Mattheissen 2014, p.207). Like Verbal processes, most of the Mental processes occur in the second part of the chapter, in which the narrator descibes Lymie’s experience reading the book and his and his father’s impressions about the other customers in the restaurant.

Behavioural processes (7, 3.64%) represent psychological and physiological activities: talking, laughing, watching, reading, etc. According to Halliday, these processes exist somewhere between Mental and Material processes (Eggins 2004, p.233). Most of these occurrences appear in the second half of the chapter, after Lymie’s arrival at the restaurant.

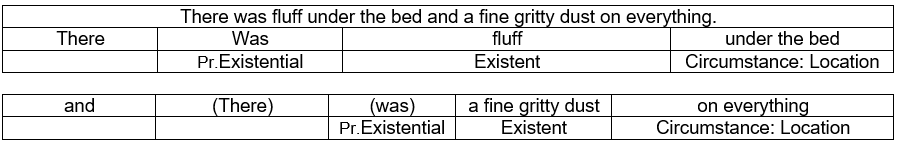

Existential processes (7, 3.64%) represent phenomena that happen or exist in the objective world (Sellami-Baklouti and Fontaine 2018, p.385). Each consists of an Existential “there”, a process expressed through verb to be, and an existent. The example below shows the only occurrence of implicit “there” and “be”. All seven Existential processes appeared in the narrator’s discourse as part of describing the surroundings of Lymie and the periods of silence that occurred during his conversation with his father.

In contrast to Mental, Verbal, Behavioural, and Existential processes, which appeared the most in the second half of the chapter, Material and Relational are common throughout the chapter and they are the main constituents of the first half of the text. The graphs below compare the frequency of the six types of processes when the chapter is divided into ten units (as seen in the text before the article).

- Transitivity and POV

In fiction writing, there are four types of POVs: temporal, spatial, psychological, and ideological (Simpson 1993). This part of the paper investigates the relationship between the observed Transitivity patterns and the Spatial and Psychological POVs manifest in the text. Spatial POV is what the characters or the narrator sees, as communicated by the author to the reader through grammatical constructions. “meaning draws on experiences we have with our bodies, including visuo-spatial experience, and meaning construction relies on cognitive processes whose primary domains are those involved in such experiences, including vision, spatial cognition and motor control” (Hart 2016, p.4).

On the other hand, Psychological POV can be described as how events are told through the lens of a certain character’s consciousness. This psychological lens can be of an omniscient narrator, limited narrator, or a single character with restricted view of reality (Simpson 1993, p.10). In other words, we speak of a Psychological POV when the author’s POV relies on an individual’s perception or consciousness (Uspensky 1973, p.81).

The first three paragraphs (unit 1, titled “Mr. Peters’ Apartment” in the text before the article) give a thorough description of the room, not from the perspective of an omniscient narrator but from the restricted POV of Lymie Peters, the protagonist of the story, himself. Two arguments can lend cumulative support to this claim; the first is William Maxwell’s description of himself as a writer of autobiographical fiction (Maxwell and Burkhardt 2012, p.7). There seem to be many commonalities between Lymie’s life and Maxwell’s own teenage years, some of which are the locations he describes in The Folded Leaf, such as Devon Avenue and Sheridan Road (Maxwell and Burkhardt 2012, p.65). It seems that Maxwell employed many autobiographical elements in writing The Folded Leaf to the point of saying that when he read his novel he “had a hard time distinguishing what is invented and what actually happened” (Maxwell and Burkhardt 2012, p.65).

The second argument in favor of a restricted POV is the use of modality and the correlative either/or to cast doubt on some of the surrounding details. In describing the lady in the photograph, the narrator says “She had a black velvet ribbon around her throat, and her dress, of some heavy material that could have been either satin or velvet, was cut low on the shoulders”. Here, modality and the correlative either/or are used to communicate what Lymie himself saw and how confused he was about the fabric of the dress: whether it was satin or velvet. Another similar instance of using modality and “or” to convey Lymie’s Psychological POV is when the narrator described the animals in the design of the rug as “dancing animals—dogs, possibly, or deer”.

Thirty five processes can be found in the first three paragraphs, most of which are Material (18, 51%) and Relational processes (11, 31%). In these 35 processes, Lymie is the actor and the senser only 5 times (14.3%). In the other 30 processes, the actors and carriers are the objects in the room (85.7%). Except for turning on the light, Lymie isn’t involved in any action with the objects in the room. After turning the light in the third paragraph, a better description is given for the rug and its design; also the time on his grandfather’s clock becomes visible, which also can lend more strength to the claim that the author is intending to manifest Lymie’s Spatial POV in the text, not the POV of an omniscient narrator who is transcendent and whose POV is unaffected by the narrated events.

Unit 4 describes Lymie’s arrival at the Alcazar Restaurant. The whole paragraph focuses on the description of the restaurant and the history book Lymie reads. Twelve processes can be found in the paragraph, 7 (58.3%) of which are Material processes, 4 (33.3%) are Relational, and 1 (8.3%) is Existential.

Just as observed in unit 1, in unit 4 Modality is used to express Lymie’s POV. After setting down at the second table from the cash register, Lymie opens the history book, and the narrator describes the book as seen by Lymie himself. The book is clearly a second hand; Maxwell uses the passive voice to obscure the Actor in “Blank pages front and back were filled in with maps, drawings, dates, comic cartoons, and organs of the body,” from which it can be understood that it is not Lymie who put these writings and drawings into the book. When describing the notations on the margins of the book, the narrator is uncertain about whether they are in ink or hard pencil; also, the narrator is ignorant about the cause of the water marks on page 177. A restricted POV, Lymie’s visual/spatial and psychological POV, is expressed through the use of uncertainty about the doer of the actions (the actor), the material used in writing, and cause of the water marks.

Unit 5 is about Lymie’s experience reading a book. In this part Maxwell encodes the Psychological POV of Lymie in grammar to show the extent to which he is absorbed in reading the book. To achieve this, the narrator describes how Lymie reads the book while eating, but instead of putting Lymie in the position of the Actor, Lymie is replaced by the synecdoche “his right hand”. In Language and Control (2019, p.200), Fowler et al. explain that the subject + verb + object structure is always used to create the illusion of agency. By locating Lymie’s right hand in the position of the Actor, Maxwell aims at denying Lymie awareness of his action due to being so focused reading the book.

As mentioned in the introduction, Halliday observed Transitivity patterns in Golding’s novel, but Halliday concluded, according to Butt and Lukin, that Golding used these patterns unconsciously (2009, p.196). However, in the case of Maxwell’s style, it can be argued that Maxwell was well aware of the patterns he used. This can be clearly observed in more than one instance where after using Transitivity patterns to achieve his goals he clarified what he meant by them in the following sentences. After positioning “the right hand” as the Actor in the Material process, the upcoming sentence says: “Sometimes he chewed, sometimes he swallowed whole the food that he had no idea he was eating.” Two similar instances will be discussed in units 6, 8, and 10.

By the end of unit 5, Lymie is reading about the Peace of Paris and counts the attendees of the congress on his left hand. In unit 6, four customers arrive at the restaurant and Lymie gets so distracted by their laughter, voices, and, though not clearly mentioned, looks. Suddenly, Lymie ceases being the Actor nor the Carrier, and every mention about the book and its content is muted; instead, the two men and the two women become the focus of the sentences. This change in pattern is used to convey Lymie’s Psychological POV, being focused on the arriving customers instead of the book at hand.

As in “the right hand” example in unit 5, Maxwell concludes the change in pattern by highlighting its purpose. This sudden change in the grammatical Transitivity patterns from Lymie and his book to the part of four reflects Lymie’s attention that is unwillingly directed towards them. This lack of attention causes him to lose track of where he was in the book and to inattentively move his eyes over the text without comprehending what he is reading. When Lymie finally realizes the two pages he missed, he goes back to read them carefully, and the focus immediately reverts back to the contents of the book.

One of the best examples of the playful use of Transitivity and restricted POV appear at the end of unit 6. Lymie is focused again and reads the pages he missed, but before finishing them, the narrator says, “a coat that he recognized as his father’s was hung on the hook next to his chair.” Maxwell obscures the true agent, the father who hangs the coat on the hook, and, using passive voice, Maxwell brings the coat to the beginning of the clause. Then, he bases Lymie’s recognition of his father’s arrival on seeing the coat before seeing the father. By using passivization, Maxwell weakens the link between the agent (Mr. Peters) and the action (hanging the coat) (Hart 2011, p.174 quoting Hodge and Kress 1993, p.26). This structure can only be understood in terms of helping the reader imagine Lymie’s Spatial POV: he is setting reading the book placed on the table; the father arrives, but Lymie cannot see him because he is looking down at the book. The first thing, other than the book, that Lymie notices within his visual field, maybe with the corner of his eyes, is a coat being hung on the hook next to his chair. Lymie immediately realizes that his father has arrived. Maxwell managed to encode a detailed description of both Lymie’s Visual and Psychological POVs in one skillfully designed clause.

Unit 8 describes Mr. Peters’ appearance. The first paragraph includes 9 processes; Mr. Peters is an actor in only 2 of the 9. In the other 7, elements of aging take precedence as Actors, Carriers, or Tokens and overshadow Mr. Peters, who is brought to the background as the target of all the changes that happened. Mr. Peters’ removal from agency indicates his Psychological POV, specifically his lack of awareness that he is aging. For the third time in the same chapter, Maxwell comments right after the last clause in the pattern and adds a key clause to make the meaning he encoded in the paragraph explicit: “Apparently he (Mr. Peters) himself was not aware that there had been any change.”

The second paragraph of unit 8 narrates how Mr. Peters, who is not aware that he is aging, tries to attract the attention of the women setting at the next table. Now Mr. Peters becomes the Actor, and Maxwell uses the Manner Circumstance “self- consciously” to contrast his lack of awareness of aging to the attention he gives to the ladies around, Irma the waitress and the two women at the next table.

Mr. Peters Psychological POV, not being aware of his age, is depicted as the young Mr. Peters in the second half of the second paragraph of unit 8. In the last few clauses, young Mr. Peters is the one to blame for the unseemliness of old Mr. Peters’ behaviour. This is grammatically achieved by making young Mr. Peters the actor of material processes where old Mr. Peters is the Goal.

In unit 10, Lymie and Mr. Peters are setting at the table, barely talking. Irma brings the food for Mr. Peters, but before he takes the first bite, he bends forward “so that he could see inside the necklace of Irma’s uniform”. In the following clause, Mr. Peters is not in the Actor’s position, and instead of him the fork becomes the Behaver: “The fork remained poised.” Just as with the aforementioned similar patterns, Mr. Peters is denied agency; a Transitivity pattern aimed at communicating Mr. Peters Psychological POV, being distracted from eating and unaware of the process he was engaged in. A moment later, he attempts to eat again, but once more he notices a man and a woman entering the restaurant and turns to look at the woman’s legs. The following clause, again, avoids his agency by removing him from the Actor’s position: “The liver fell off the fork.”

- Affect Criticism and The Representation of Women

Appraisal, or evaluative expressions, is one of the discursive strategies, along with pronouns, metaphors, and applause (Cap and Okulska 2013, p.270), and it belongs to the interpersonal metafunction. The Appraisal Theory analyzes Attitude, Engagement, and Graduation. According to White (Paltridge 2012, p.133), Attitude analysis is be divided into Affect, Judgement, and Appreciation; Engagement into Contract and Expand; and Graduation into Force and Focus. According to Martin and White (Oteiza 2017, p.457), “the purpose of developing an appraisal framework was to expand traditional accounts regarding issues of speaker/writer evaluation, certainty, commitment and knowledge, and also to consider how the textual voice positions itself with respect to other voices and other positions in the discourse”. Therefore, Appraisal Analysis is concerned with the rhetorical effects and meaning in context, rather than focusing on the grammatical structures and patterns.

Fiehler (2002) proposed a model for “Emotion Expression and Thematization.” This model understands emotions as communicative phenomenon (2002, p.79). In this model, though mainly concerned with conversations, the emotion/affect is turned into the theme of the interaction (2002, p.86). Also, according to (Planalp and Knie 2002, p.63), emotions can be studied from a rhetorical POV, whereby “the social situation (including the relationship between the two partners in the interaction) is the focus, and communicating emotion is a way to negotiate that situation.” Building upon these insights from Fiehler and Planalp and Knie, this part of the research focuses on the attitude towards women and how they are emotionally evaluated within the context of the narrative. In some of the instances, Affect is encoded in a situation or a grammatical structure, while in some others it is encoded in lexis.

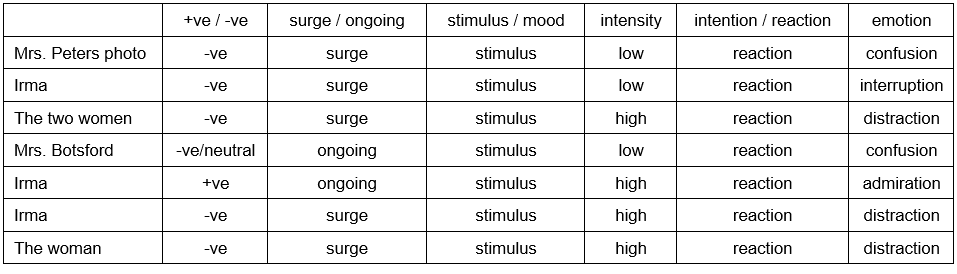

Six women were mentioned in the text: Mrs. Peters, Irma (the waitress), the two unnamed women who accompanied the two men at the table next to Lymie, Mrs. Botsford who used to work for Mr. Peters, and the unnamed woman who came in to the restaurant at the end of the chapter. To evaluate how these six women are represented in the text, the research will ask the first five of the six questions recommended by Martin and Rose (2007, p.64). These questions cover many aspects: (1) whether the feelings are positive or negative, (2) whether emotions are represented as a surge or as an ongoing mental state, (3) whether emotions are a reaction to an external stimulus or an ongoing mood, (4) whether they are more or less intense, and (5) whether they involve an intention or reaction. The sixth question was amended because as proposed by Martin and Rose it is limited to feelings of un/happiness, in/security, and dis/satisfaction, which are not directly relevant to the emotions manifest in the text.

Lymie has a picture of his mother in his room. It is clearly understood from the chapter that Lymie has never met his mother; he has no memory of her and knows her only through the picture, which was the work of a photographer who edited an old photo. The narrator states that this photograph confused Lymie instead of reminding him of how his mother had looked like.

Irma appears on the list twice, the first instance happens when Lymie puts his fork to count the attendees of congress of Vienna on the fingers of his left hand. Irma thinks he is done eating and tries to take his plate, but his signals her to stop. Although there is no clear mention of an emotion in this instance and Lymie isn’t indeed distracted, Irma’s representation as an interruption can be seen in the light of the pattern of the negative affect of women in the chapter.

The party of four, the two men and the two women, who came into the restaurant and sat on the table nearest Lymie are represented negatively; however, women are represented more negatively than men are. No mention at all of the men’s appearance, whether they were drunk, and their effect on Lymie. On the other hand, women are represented negatively and are harshly criticized: one is shamed for her body, and the other is shamed for her, according to the narrator, not too feminine facial features and for using too much make up. The behaviour of the whole group is described as noisy, but only the women’s voices were deemed terrible and not quite sober. Finally, only the women voices were a distraction for Lymie, while the text is silent about any negative influence for the men over Lymie.

During Mr. Peters’ conversation with Lymie, he asks Lymie whether Mrs. Botsford has come. Lymie responds negatively and excuses her for the possibility of being sick. On the other hand, although Mr. Peters credits Mrs. Botsford for informing him whenever she is sick, he thinks she could have quit the job without a notice because she lives far from work. Two impressions can be received from the text about Mrs. Botsford. The first is at best neutral: she had to leave because of the daily long journey from where she lives to where she works. The second is that she is an unreliable employee who did not care to inform the employer so that he can have time to look for a replacement. In either case, the reader is left confused over the reason for her absence, just as Mr. Peters and Lymie are.

The last three instances are very similar, a lady appears and Mr. Peters is suddenly distracted from eating while looking at her. The three instances involve two ladies, the first of whom is Irma; she brings the food to Mr. Peters, and when she leans across the table to put the glass of water in front of him, he forgets about food and says “Irma is a very fine girl. Too capable to be doing this kind of work. She ought to be in an office somewhere making twenty- five dollars a week.” Although Irma is viewed positively in this instance, the word “fine” can be understood to mean either “beautiful” or “efficient”, but when read in the light of what follows in the chapter (Mr. Peters’ attempt at seeing inside the neckline of Irma’s uniform), this remark of Mr. Peters seems to be an indirect reference for Irma’s beauty rather than a direct reference to her work efficiency.

The second and third instances, juxtaposed in the table below, exhibit an almost identical sequence: (1) Mr. Peters is taking the first bite of his food, (2) a woman enters the scene, (3) Mr. Peters’ attention is directed to the woman, (4) Mr. Peters forgets his food, (5) Mr. Peters leaves the food aside and does not eat it. In both instances Mr. Peters seems to lose track of what he is doing once a woman is around. The author, reflecting Lymie’s POV, describes this repeated pattern as a comedy that kept going on for nearly twenty minutes. When observed along with the aforementioned Transitivity patterns (removing the person’s agency to deny him awareness or attention) as frequently seen in the case of Mr. Peters, Maxwell’s narrator seems to thematically and grammatically enforce a certain view of the feminine element as confusing and distracting in Lymie’s POV, and as distractingly charming in Mr. Peters’ POV.

- Conclusion

After analyzing the numerical findings and the charts based on the categorizing and subcategorizing the types of processes, the research focused on two major points: (1) Transitivity patterns and how they are used to convey the POVs of the narrator, Lymie, and Mr. Peters; (2) The Appraisal of women: specifically, how certain emotions, affects, are rhetorically ascribed to the main characters when they encounter women, and how this technique is used to evaluate women.

The findings of this research suggest that William Maxwell, though writing years before the proposal of the Systemic Functional Grammar by M. A. K. Halliday, used Transitivity patterns to convey, at least, two types of POV: Spatial and Psychological. The narrator, adopting Lymie’s spatial POV, is able to see better once the light was turned on by Lymie, which allowed him, the narrator, to observe the patterns on the rug and to describe them in detail. Also, Lymie, being bent down at his book, first saw the coat of his father, and, therefore, realized that it was indeed his father who joined him at the table.

The examples for Psychological POV are even more frequent. One of the most frequent Transitivity patterns used by Maxwell was to grammatically deny a certain character agency to show that this character is engaged in an intense mental activity, distracted, or confused. This was achieved by removing the person from the position of the actor, senser, and behaver, and replacing him by an inanimate object, such as Lymie’s hand which fed him while he was not aware he was eating and the fork which held the food on Mr. Peters’ behalf when he was busy watching Irma, and as also seen in the many different examples detailed in the research. One remarkable evidence for Maxwell’s awareness of the impact of these patterns is the fact that he always explains his intention in the following sentence, a very frequent pattern that cannot be discarded as a mere coincidence within a chapter of only about 2100 words.

The second part investigated the sort of emotions the main characters experience when they encounter women. Generally, it can be said that within this chapter encountering women meant being confused, distracted, and unfocused. Although the last couple of encounters, Mr. Peters’ encounter with Irma and the unnamed woman who entered the restaurant at the end of the chapter, can be seen as a reference to the women’s beauty, their impact on Mr. Peters is definitely evaluated negatively by the narrator who describes Mr. Peters’ reaction as a comedy that lasted for about twenty minutes.

Although, to an inexperienced reader, this chapter could seem an average-level piece of writing, Maxwell showed impressive skill in encoding information in his sentences. From Psychological and Spatial/Visual POVs to Affect and Evaluation of women, Maxwell managed to depict many different aspects of the personality traits of his characters, helping the reader visualize and feel exactly what his characters are experiencing. This research expounded on how different types of Discourse Analysis based on SFG can help a reader trace the patterns an experienced author, like Maxwell, uses to turn words into living characters, vivid interactive surroundings, and psychological states that the reader can relate to and experience.

_______________________________________________________________________________

References

Butt, D. G., & Lukin, A. (2009). Stylistic analysis: construing aesthetic organisation. Continuum companion to systemic functional linguistics, 190-215.

Cap, P., & Okulska, U. (Eds.). (2013). Analyzing genres in political communication: Theory and practice (Vol. 50). John Benjamins Publishing.

Chilton, P., & Schäffner, C. (Eds.). (2002). Politics as text and talk: Analytic approaches to political discourse (Vol. 4). John Benjamins Publishing.

Coffin, C. (2009). Historical discourse: The language of time, cause and evaluation. Bloomsbury Publishing.

De Rycker, A., & Don, Z. M. (Eds.). (2013). Discourse and crisis: Critical perspectives (Vol. 52). John Benjamins Publishing.

Derrida, J. (1977). Of Grammatology. Translated by G. C. Spivak. The John Hopkins University Press.

Eggins, S. (2004). Introduction to systemic functional linguistics. A&c Black.

Fiehler, R. (2002). How to do Emotions with Words: Emotionality in Conversations (pp.79-106). In Fussell, S. R. (Ed.). (2002). The Verbal Communication of Emotions: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Psychology Press.

Fowler, R., Hodge, B., Kress, G., & Trew, T. (2019). Language and control. Routledge.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. (2013). Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar. Routledge.

Halliday, M. A. K., Matthiessen, C. M. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar. Routledge.

Hart, C. (2016). Discourse, grammar and ideology: Functional and cognitive perspectives. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Hart, C. (Ed.). (2011). Critical discourse studies in context and cognition (Vol. 43). John Benjamins Publishing.

Hodge, R., & Kress, G. R. (1993). Language as ideology (Vol. 2). London: Routledge.

Liu, Y. (2008). The construction of patriotic discourse (pp. 57-75). In Dolón, R., & Todolí, J. (Eds.). (2008). Analysing identities in discourse (Vol. 28). John Benjamins Publishing.

Matthiessen, C., Teruya, K., & Lam, M. (2010). Key terms in systemic functional linguistics. A&C Black.

Maxwell, W. (2012). Conversations with William Maxwell. Univ. Press of Mississippi.

Paltridge, B. (2012). Discourse Analysis: An Introduction (Bloomsbury Discourse). Continuum.

Planalp, S., & Knie, K. (2002). Integrating verbal and nonverbal emotion (al) messages (pp. 55-77). In Fussell, S. R. (Ed.). (2002). The Verbal Communication of Emotions: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Psychology Press.

Ritivoi, A. D. (2008). Talking the political talk: Cold War refugees and their political legitimation through style, 33-57. In Johnstone, B., & Eisenhart, C. (Eds.). (2008). Rhetoric in detail: Discourse analyses of rhetorical talk and text (Vol. 31). John Benjamins Publishing.

Sellami-Baklouti, A., & Fontaine, L. (Eds.). (2018). Perspectives from systemic functional linguistics. Routledge.

Simpson, P. (1993). Language, ideology and point of view. Routledge.

Thompson, G. (2013). Introducing functional grammar. Routledge.

Uspensky, B. A. (1973). Study of Point of View: Spatial and Temporal Form. Centro internazionale di semiotica e di linguistica, Università di Urbino.

Zdenek, S., & Johnstone, B. (2008). Studying style and legitimation. In Johnstone, B., & Eisenhart, C. (Eds.). (2008). Rhetoric in detail: Discourse analyses of rhetorical talk and text (Vol. 31). John Benjamins Publishing.

Very interesting info!Perfect just what I was searching

for!